Only one came home

On the Royal Air Force’s worst night ever, my great uncle and six other airmen aboard a Halifax bomber left for a mission over Germany. Within hours, six were dead.

One of my most-rewarding projects in journalism was creating a Twitter/X bot called @WeAreTheDead, which tweets the name of a Canadian Forces member who died in service, every hour at 11 minutes past the hour. The Ottawa Citizen has continued the tradition of researching and writing a profile of the Forces member whose name is selected at random and tweeted at 11:11 on Remembrance Day. The profile takes quick research to find out how, when and where each died. With help from crowdsourcing, the reporters dig up as much as they can about the soldier, sailor or aviator, to put a face on one of 119,000 Canadians who died protecting our country. The Citizen will reprise the project again on Saturday. But this year, I wanted to add a more personal story.

The moon shone bright on North Yorkshire as a Halifax III bomber took off from the Royal Air Force base at Skipton-on-Swale, a little after 9:30 p.m. on March 30, 1944.

The mission: a bombing run over Nuremberg, part of a massive push to destroy German industrial capacity and munitions manufacturing before the coming Allied landing in Normandy.

The Halifax was one of the 795 aircraft in the sky crossing over the English Channel; 95 planes would never return.

Military historians would later question the decision by the head of Bomber Command, Sir Arthur Harris, to send aircraft without cloud cover to hide them from anti-aircraft fire or German fighters. The result was the greatest loss — 545 airmen — the Royal Air Force had seen in a single day.

The Halifax was crewed by seven young Canadian and British airmen. Sitting in the navigator’s seat, guiding the flight through the darkness toward their target, was my great uncle, Flying Officer John “Jack” Mason, age 28.

Within hours of take-off, all but one was dead.

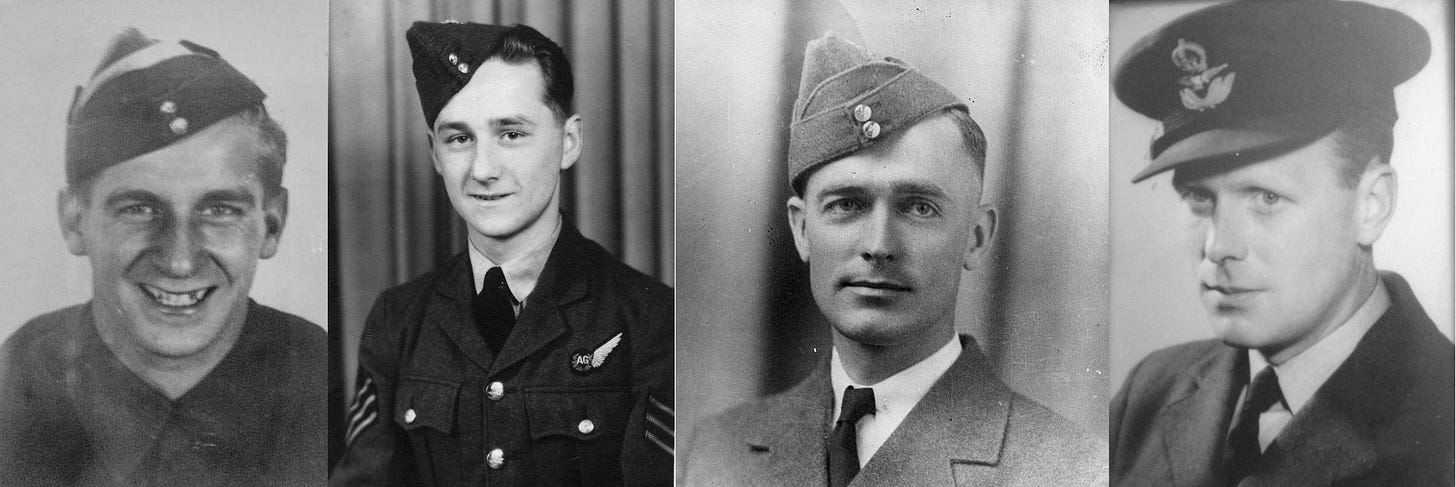

Also aboard the Halifax that night:

The pilot, Flying Officer John Doig, age 31, from Winnipeg, Manitoba;

Pilot Officer Robert Atkins, 27, from Petrolia, Ontario;

The radio operator, Sgt. Donald Stewart, 22, from Finsbury Park, England;

The fight engineer, Sgt. John Bolton;

The tail gunner, Sgt. Thomas Rogers, from Carmarthenshire, Wales;

The air bomber, Warrant Officer Alfred Crosland, 22, from Pickering, Ontario;

Jack Mason was the son of a customs broker. He grew up in the Beaches in Toronto and graduated from high school at Scarborough Collegiate. His parents, Thomas and Gertrude Mason, lived at 153 Courcelette Road, named for another bloody battle Canadians fought in France in the First World War.

Mason was a skilled sailor, a member of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club and the Beaches Masonic Temple. Before the War, he worked for a time selling men’s clothing, and later, as a broker alongside his father. He enlisted in January 1942 and went off to train at the air base in Malton, Ontario.

He was tall, dark-haired and handsome, with a thin pencil moustache that made him look a bit like a young Errol Flynn.

Jack was assigned to the 424th “Tiger” Squadron. Arriving in England, he first stayed at the London YMCA, which he described in a letter home as “a wonderful place… opened last week by the Duke of Gloucester.”

In his letters, he never mentioned where he was eventually stationed in England but he left some clues.

“Yesterday, I spent a glorious afternoon on the moors,” he wrote to his parents, my great grandparents, in late 1943 .

“We had class all morning, then this afternoon, Bill and I pedalled around for 20 miles, stripped to our shorts again, through little fishing villages, old towns, up and down wicked hills but hard work and good fun and exercise.”

He’d received a wedding notice and photos from his parents of his sister, Marjorie, an Orpheus singer who in had married an Ottawa artist, Sub-Lieutenant Gordon Stranks — my grandparents.

“Doesn’t Marj look great in her wedding outfit,” Jack wrote back.

“Gordon certainly looks like a fine type. I like the cut of his jib.”

Jack hadn’t been able to come home for the wedding in October 1943 at St. John’s Norway Anglican church in the Beaches.

“When I saw the pictures and clippings, I’m afraid I was really homesick.”

A month before what would be his final mission, Jack wrote home expressing weariness with life on the base.

“With the exception of one evening in Scarborough, things have remained pretty dull,” he wrote.

“Here it is Saturday afternoon and instead of looking forward to a nice weekend, I have visions of it here in this mud hole, jumping from one fire to another to keep warm.”

There was never any reference to the missions he’d flown on — military secrecy — but in one letter, he said he hoped to fly on pathfinder flights.

“They go in to the target alone and before anyone else to light up the aiming point for the regulars. You have to be really good to make [it], so I’ll be lucky.”

Jack and the crew of the Halifax were not so lucky over Germany.

Around 12:30 am on March 31, they were shot down by a German fighter. The flaming wreckage of the aircraft fell into a field near Alten-Buseck, a hamlet north of Frankfurt.

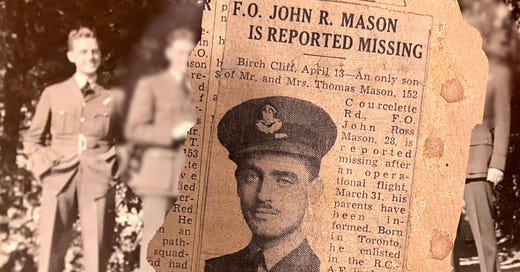

Jack was reported missing, but not yet presumed dead.

Some days later, a short item in a Toronto newspaper, accompanied by Jack’s official RCAF photo, reported that his family had been told the worrying news.

For the Mason family, this began an agonizing wait for more information.

A letter in June 1944 to the Masons from another RCAF member, a friend of Jack’s in England, didn’t sound promising.

“I share your grief,” wrote “Chum” Mackenzie. “I know you are hoping and praying for the best and I’m afraid this is all that can be done.”

Mackenzie cautioned that details about missing airmen behind enemy lines can sometimes come slowly.

“In this momentous time, no news is good news… I don’t want to build up false hopes for you but I do want you not to give up for some time yet.”

Four months later, in July 1944, the International Red Cross contacted the Mason family: Jack was alive and listed as a prisoner of war.

A telegram sent to the RAF casualty branch a month later reported that British intelligence had obtained German documents describing the air battle. The Halifax, they learned, had “disintegrated at very great height and was scattered over an area of 1 km.”

Though Jack had survived, “Remainder all dead. Buried in Alten Busek cemetery.”

Jack was the only crew member who managed to bail out of the stricken aircraft. He had parachuted into a tree, injuring his leg. A German police officer had helped him climb down.

Jack would later tell his family that the policeman had spotted his Masonic ring. As a fellow Freemason, he treated the prisoner well before turning him over to military custody, Jack maintained.

Sometime later, Jack was transferred to Stalag Luft III, a P.O.W. camp for Allied airmen.

Only a few weeks before, a group of Canadian, British and American flyers had escaped the camp through tunnels they had secretly dug. Though 76 made it out, all but three were recaptured; 50 were executed by firing squad, a lesson for the P.O.W.s still behind the wire. When Jack Mason arrived, several weeks after “The Great Escape,” the prisoners were confined to their bunks.

News of Jack’s well-being came sporadically through the Red Cross.

But in September, his family received dozens of hand-written notes from members of a network of short-wave radio hobbyists who listened in to German transmissions.

“Last night, short-wave Radio Berlin broadcast a medical report about your son,” read one sent to his father. “His right ankle was broken. Functional follow-up treatment is being given. He is getting exercise to put him in good shape.”

Similar hand-written cards came from short-wave listeners in Brooklyn, Detroit, Indiana, Florida and Pennsylvania.

Jack would later describe life at Stalag Luft III in a letter to the parents of another P.O.W. in Manitoba. Prisoners received six or seven loaves of black bread each week, he said, along with sugar, margarine, barley and sometimes blood sausage.

Life in the camp was “grim,” but still a “never-to-be-forgotten experience.”

He described the ingenuity of the P.O.W.s showed building an improvised theatre, with seats fashioned from Red Cross crates and lights made from milk tins. They entertained themselves with a theatrical troupe and three orchestras — concert, symphony and swing.

Clothing was a problem, though. “Everyone in camp could use a pair of good stout boots, as the sandy soil there played havoc with the leather,” he wrote, possibly a glancing reference to the yellow sand that had made tunnelling difficult for the Great Escapists.

Jack was eventually released from the Stalag Luft III on January 5, 1945, as part of a prisoner swap negotiated by Switzerland. He came back to Canada on the repatriation ship Gripsholm.

His return to Toronto was documented in the papers. He was pictured, looking dashing in formal dress uniform, smoking a cigarette and chatting up lady socialites at galas.

Jack would go on to work for the Imperial Life insurance company. He continued to sail and served as fleet captain of the RCYC and master of his Masonic Lodge.

As a kid fascinated by military history, I often asked about his service. He gave me his leather air crew helmet and goggles for a Hallowe’en costume one year, but never stories about the war.

Jack died of natural causes in Toronto in 1986.

I learned more only two weeks ago, when his widow, Barbara, sent me a scrapbook with the yellowing newspaper clippings and letters I’ve quoted above. I called her to ask for some missing details.

But as she explained, “He just didn’t like to talk about it.”

On Saturday, I’ll raise a glass to Flying Officer John Ross Mason, and the other members of the crew, who never returned, like so many others who flew over Germany that night.

Thank you for writing this. The pilot John

"Jack" Doig was my grandpa's oldest brother.

Thank you for sharing this Glen and for all your selfless work on @wearethedead