There shall (not) be blood

For Hallowe'en, a slightly ghoulish tale about prime ministerial plasma

On my first trip aboard the Royal Canadian Air Force jet used to transport the prime minister overseas, in 2016, I noticed a strange appliance perched on a seat in the back row of the cabin.

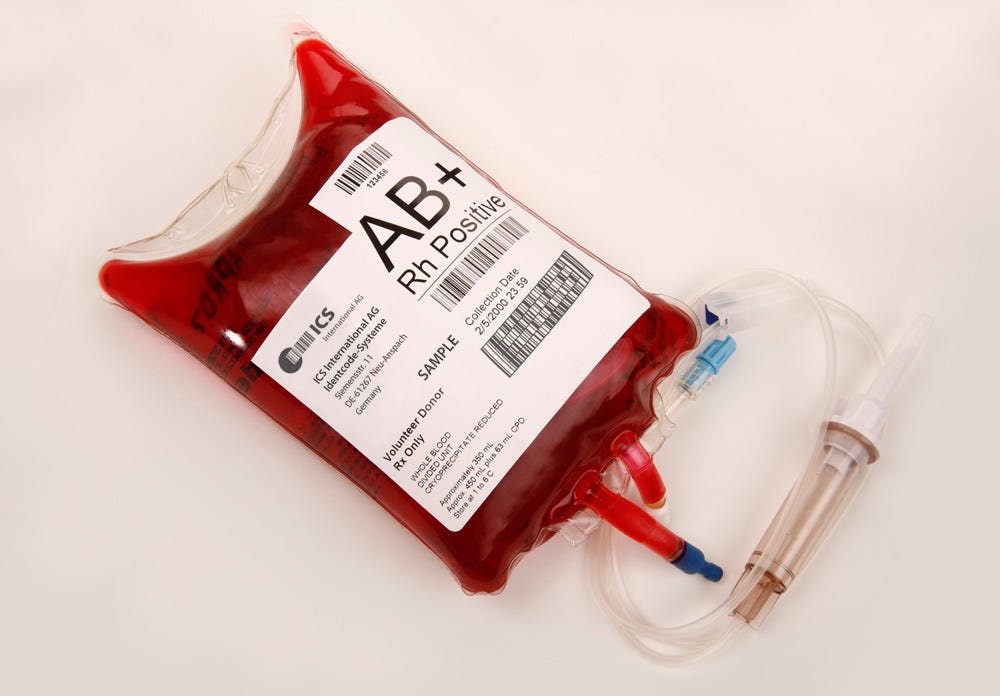

It looked a bit like a militarized bar fridge: beige, squat, with a heavy plastic casing, glowing LED lights and an extension cord connected to a power supply.

I asked another reporter who had travelled with the PM before about the curious device.

“The blood,” he mouthed in a stage whisper, and said nothing more.

The blood?

Upon further inquiry, I learned that, sometime since the late 1980s, Canadian prime ministers travelling abroad have sometimes carried with them their own supply of blood plasma.

The measure would ensure that, were the PM or anyone else in the Canadian delegation injured, medical staff would have a safe source for a transfusion readily available.

The idea appears to date back at least to January 1987, when then-Prime Minister Brian Mulroney was about to make an official visit to Zimbabwe and Senegal.

At a pre-trip briefing for journalists, Mulroney’s aides caused a minor furor when they said that the PM would take blood plasma on the trip because of the worry about the reliability of the supply on a continent ravaged by the AIDS epidemic.

The blood would be available to the prime minister and his wife, and to the approximately 60 aides, journalists, and other officials scheduled to travel with them, Mulroney’s staff explained.

Not mentioned by the Prime Minister’s Office was the US practice of ensuring that there is a safe blood supply close at hand whenever POTUS leaves the White House. That seemed to date to the 1981 attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan outside a Washington, D.C., hotel. Since the Trump era, and maybe earlier, the president’s armoured limousine, the Beast, has been said to have a blood fridge aboard.

But in an odd turn-around, Mulroney’s press secretary, Michel Gratton, contacted The Canadian Press the day after the press briefing to say it had all been a misunderstanding. PMO staff had (quite reasonably) misconstrued inquiries from the Canadian Armed Forces about their blood types.

In fact, explained spokesman Marc Lortie, there would be no blood plasma on the Africa trip.

Dismissed as groundless was the speculation that Mulroney, known to be fastidious in matters of personal hygiene, was concerned about the safety of a transfusion in Africa.

An official with External Affairs told CP that, had Mulroney brought blood, he would have been the first prime minister to do so.

Nevertheless, at some point later, PM delegations did, in fact, begin travelling with a blood supply.

When I asked about it much more recently, staff in Justin Trudeau’s office were alternately baffled then squeamish. They didn’t seem know a lot about it and wouldn’t say much of what they did.

Trudeau, I learned, was also unaware of the refrigerator on the plane or the IV bags inside. That suggested he didn’t have to donate to his own supply before flying. It was obtained from another source.

Then, at some point, the practice was suddenly discontinued.

On Trudeau’s own trip to Senegal and other African destinations in early 2020, just as the first outbreaks of the COVID-19 virus were appearing, I noticed that the blood fridge wasn’t in its usual place at the back of the Airbus 310.

A source familiar the issue told me that the Canadian Armed Forces decided travelling with blood plasma — then flushing it all after the trip — wasn’t a good use of such a valuable resource.

The scarce supply could be better used to help cancer patients or trauma victims in Canadian hospitals, rather than waste it on the remote chance it would be required by the travelling delegation.

Canada’s lengthy military deployment to Afghanistan may have informed some of this thinking. The CAF learned it wasn’t efficient to refrigerate large quantities of blood when there were hundreds of potential donors on base in Kandahar, keeping it refreshed in their own bodies.

A walking blood bank, even in a war zone, was a more dependable source.

The delegation that prime minister takes abroad, often numbering in excess of 100, is sufficiently large to constitute a mobile blood bank of it its own.

A bizarre quirk of this arrangements is that journalists who accompany the PM could — in the unlikely chance of a serious incident — be called on to the give the gift of life to someone they report on daily.